Unpacking Antinatalist Philosophy: Why Some Think Existence Is a Harm and Procreation Is Unethical. Explore the Arguments, Controversies, and Implications of This Provocative Worldview.

- Introduction: Defining Antinatalism

- Historical Roots and Key Thinkers

- Core Arguments Against Procreation

- Ethical Frameworks in Antinatalism

- Psychological and Existential Dimensions

- Critiques and Counterarguments

- Antinatalism in Literature and Culture

- Legal and Societal Implications

- Contemporary Movements and Advocacy

- Future Directions and Philosophical Challenges

- Sources & References

Introduction: Defining Antinatalism

Antinatalism is a philosophical position that assigns a negative value to birth, asserting that bringing new sentient beings into existence is morally problematic or undesirable. Rooted in ethical, metaphysical, and existential considerations, antinatalism challenges the commonly held assumption that procreation is inherently good or neutral. Instead, antinatalists argue that coming into existence inevitably exposes individuals to suffering, harm, and deprivation, and that these negative aspects outweigh any potential benefits of life.

The origins of antinatalist thought can be traced to various philosophical and religious traditions. In Western philosophy, figures such as Arthur Schopenhauer and Peter Wessel Zapffe articulated early forms of antinatalist reasoning, emphasizing the pervasive nature of suffering and the futility of human striving. In contemporary philosophy, David Benatar is a prominent advocate, particularly known for his “asymmetry argument,” which posits that while the absence of pain is good even if there is no one to benefit, the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone for whom this absence is a deprivation.

Antinatalism is not a monolithic doctrine; rather, it encompasses a range of arguments and motivations. Some proponents focus on the ethical implications of causing suffering, drawing on principles of harm reduction and consent. Others emphasize environmental concerns, such as the impact of human population growth on planetary resources and non-human life. There are also metaphysical and existential variants, which question the value or meaning of existence itself.

While antinatalism remains a minority view, it has gained increased attention in academic and public discourse, particularly in the context of global challenges such as climate change, overpopulation, and animal welfare. Philosophical societies and academic journals have engaged with antinatalist arguments, fostering debate about the moral status of procreation and the responsibilities of prospective parents. Organizations such as the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provide comprehensive overviews of antinatalist theories, reflecting the growing scholarly interest in this field.

In summary, antinatalism is a complex and evolving philosophical stance that interrogates the ethics of birth and existence. By questioning the assumed value of procreation, antinatalism invites deeper reflection on suffering, responsibility, and the broader consequences of bringing new life into the world.

Historical Roots and Key Thinkers

Antinatalist philosophy, which argues that bringing new sentient life into existence is morally problematic or undesirable, has roots that stretch back to antiquity, though it has only recently been formalized as a distinct philosophical position. The core idea—that procreation may be ethically questionable—has appeared in various forms across cultures and eras.

In ancient Greece, the pessimistic outlook of philosophers such as Hegesias of Cyrene (c. 300 BCE) foreshadowed antinatalist themes. Hegesias, sometimes called the “Death-Persuader,” argued that happiness is unattainable and that non-existence is preferable to life’s inevitable suffering. Similarly, in ancient Indian philosophy, certain strands of Buddhism and Jainism emphasized the cessation of rebirth and the escape from the cycle of suffering, which can be interpreted as proto-antinatalist in spirit.

The modern articulation of antinatalism, however, is most closely associated with the work of South African philosopher David Benatar. In his influential book “Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence” (2006), Benatar presents the “asymmetry argument,” which posits that while the presence of pain is bad and the presence of pleasure is good, the absence of pain is good even if there is no one to benefit from that good, whereas the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone for whom this absence is a deprivation. This reasoning leads Benatar to conclude that coming into existence is always a harm, and thus procreation is morally questionable.

Another significant figure is the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), whose philosophical pessimism deeply influenced later antinatalist thought. Schopenhauer viewed life as characterized by suffering and desire, with non-existence as a preferable state. His works, particularly “On the Suffering of the World,” have been cited as foundational to the antinatalist worldview.

In the 20th century, Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran further developed antinatalist themes, expressing profound skepticism about the value of existence and the wisdom of procreation. Cioran’s aphoristic writings, such as “The Trouble with Being Born,” reflect a radical doubt about the worth of life itself.

While antinatalism remains a minority position, it has gained attention in academic philosophy and bioethics, with ongoing debates about its implications for reproductive rights, environmental ethics, and the future of humanity. Organizations such as the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy provide comprehensive overviews of antinatalist arguments and their historical development.

Core Arguments Against Procreation

Antinatalist philosophy is grounded in a set of core arguments that challenge the ethical permissibility of procreation. Central to antinatalism is the belief that bringing new sentient life into existence is morally questionable, primarily due to the inevitability of suffering and the absence of consent from the potential person. These arguments are articulated by philosophers such as David Benatar, whose work “Better Never to Have Been” is foundational in contemporary antinatalist thought.

One of the principal arguments is the asymmetry argument, which posits that while the presence of pain is bad and the presence of pleasure is good, the absence of pain is good even if there is no one to benefit from that good, whereas the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone for whom this absence is a deprivation. This asymmetry leads to the conclusion that not bringing someone into existence prevents harm without depriving anyone of pleasure, thus making non-procreation ethically preferable.

Another significant argument is the consent argument. Since a person cannot consent to being brought into existence, procreation imposes life—and by extension, suffering—on an individual without their permission. This lack of consent is seen as a moral failing, especially given the risks and harms inherent in life, including disease, psychological distress, and eventual death. The World Health Organization and other health authorities document the prevalence of suffering and disease globally, underscoring the inevitability of harm in human life.

Antinatalists also invoke the environmental and ethical argument, which highlights the impact of human procreation on planetary well-being. The continued growth of the human population exacerbates resource depletion, environmental degradation, and climate change. Organizations such as the United Nations have repeatedly emphasized the strain that population growth places on global resources and ecosystems, further supporting the antinatalist position that refraining from procreation can be seen as an ethical response to ecological crises.

Finally, antinatalists argue that procreation is not a necessity for personal fulfillment or societal progress. They challenge the assumption that having children is an inherent good, suggesting instead that meaning and value can be found in other pursuits. This perspective is supported by philosophical and psychological research into well-being and life satisfaction, which shows that fulfillment is not exclusively tied to parenthood.

Ethical Frameworks in Antinatalism

Antinatalist philosophy is grounded in the ethical evaluation of procreation, asserting that bringing new sentient beings into existence is morally problematic or unjustifiable. The ethical frameworks within antinatalism are diverse, but they generally converge on the principle that non-existence is preferable to existence due to the inevitability of suffering. This position is often contrasted with pronatalist views, which regard procreation as a moral good or neutral act.

One of the most influential ethical frameworks in antinatalism is the asymmetry argument, articulated by philosopher David Benatar. According to this view, the presence of pain is bad, and the presence of pleasure is good; however, the absence of pain is good even if there is no one to benefit from that good, while the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone for whom this absence is a deprivation. This asymmetry leads to the conclusion that it is better never to have been born, as non-existence avoids harm without depriving anyone of pleasure (University of Oxford).

Another ethical approach within antinatalism is rooted in utilitarianism, which evaluates actions based on their consequences for overall well-being. Antinatalist utilitarians argue that since life inevitably involves suffering—ranging from physical pain to psychological distress—refraining from procreation minimizes harm and is therefore the ethically preferable choice. This perspective is informed by empirical research on global suffering and quality of life, as documented by organizations such as the World Health Organization.

Some antinatalist arguments are also informed by rights-based ethics, emphasizing the inability of potential persons to consent to being born. This framework posits that imposing existence, with its attendant risks and harms, on a non-consenting being is ethically questionable. The notion of consent is central to many contemporary human rights discussions, as reflected in the work of bodies like the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

In summary, antinatalist philosophy draws on a range of ethical frameworks—including asymmetry arguments, utilitarianism, and rights-based ethics—to challenge the moral permissibility of procreation. These frameworks collectively highlight concerns about suffering, consent, and the value of non-existence, forming the core of antinatalist ethical reasoning.

Psychological and Existential Dimensions

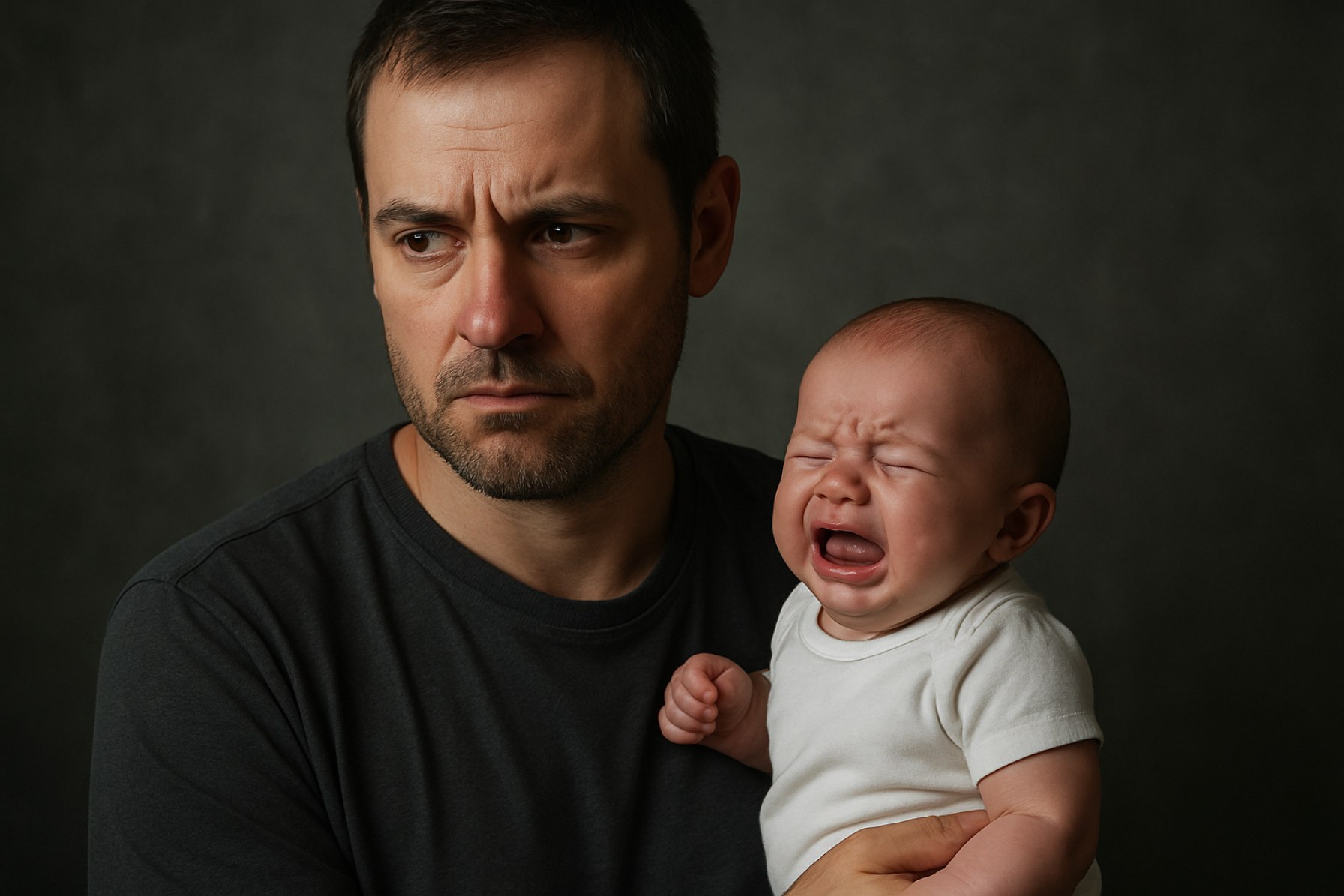

Antinatalist philosophy, which posits that bringing new sentient life into existence is morally questionable or undesirable, is deeply intertwined with psychological and existential considerations. At its core, antinatalism raises profound questions about the nature of suffering, the value of existence, and the responsibilities of sentient beings. These questions are not merely abstract; they resonate with individual and collective experiences of meaning, purpose, and well-being.

From a psychological perspective, antinatalism often draws upon the recognition of suffering as an inescapable aspect of conscious life. Influential antinatalist thinkers, such as David Benatar, argue that the harms and pains inherent in existence outweigh potential pleasures, and that non-existence spares individuals from inevitable suffering. This view is informed by research in psychology and psychiatry, which documents the prevalence of mental health challenges, existential anxiety, and the human tendency to experience dissatisfaction or distress even in favorable circumstances. Organizations such as the World Health Organization have highlighted the global burden of mental disorders, underscoring the universality of psychological suffering.

Existentially, antinatalism engages with questions of meaning and the human condition. Existentialist philosophers, including Arthur Schopenhauer and Emil Cioran, have influenced antinatalist thought by emphasizing the futility and inherent suffering of life. The existential dimension of antinatalism is not solely pessimistic; it also invites reflection on autonomy, responsibility, and the ethics of procreation. For some, the decision not to create new life is an expression of compassion and a rational response to the uncertainties and hardships of existence.

The psychological impact of antinatalist beliefs can be complex. For adherents, these views may provide a framework for understanding personal suffering and a sense of solidarity with others who question the value of existence. However, critics argue that antinatalism may exacerbate feelings of hopelessness or alienation, particularly in individuals already vulnerable to existential distress. Mental health professionals, such as those affiliated with the American Psychological Association, emphasize the importance of addressing existential concerns in a supportive and nuanced manner, recognizing the diversity of human responses to suffering and meaning.

In summary, the psychological and existential dimensions of antinatalist philosophy highlight the interplay between individual experience, ethical reasoning, and broader questions about the human condition. By foregrounding suffering and the responsibilities of sentient beings, antinatalism challenges prevailing assumptions about the desirability of procreation and the pursuit of happiness.

Critiques and Counterarguments

Antinatalist philosophy, which posits that bringing new sentient beings into existence is morally problematic or undesirable, has generated significant debate within academic and ethical circles. While proponents argue from perspectives such as the reduction of suffering and the prevention of harm, critics have raised a variety of objections, both philosophical and practical.

One of the primary critiques centers on the perceived pessimism of antinatalism. Opponents argue that the philosophy overemphasizes suffering and neglects the value and potential for happiness, fulfillment, and meaning in human life. They contend that life, while containing suffering, also offers opportunities for joy, achievement, and connection, which antinatalism may undervalue. This critique is often rooted in broader philosophical traditions that emphasize human flourishing and the pursuit of well-being, such as those articulated by organizations like the American Philosophical Association.

Another significant counterargument is the challenge to the asymmetry principle, a key tenet in some antinatalist arguments, particularly those advanced by philosopher David Benatar. The asymmetry principle suggests that the absence of pain is good even if there is no one to benefit, but the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is someone deprived of it. Critics argue that this principle is not intuitively obvious and may rest on questionable assumptions about value and harm. Philosophers and ethicists, including those associated with the British Academy, have debated whether this asymmetry can be consistently applied or if it leads to paradoxical conclusions.

Practical objections also arise regarding the implications of antinatalism for society and human progress. Critics suggest that widespread adoption of antinatalist views could undermine social structures, intergenerational responsibilities, and the continuation of cultural and scientific advancements. Organizations such as the United Nations emphasize the importance of sustainable population growth and the role of future generations in addressing global challenges, highlighting a tension between antinatalist ethics and broader societal goals.

Finally, some argue that antinatalism may inadvertently devalue the lives of those already born or lead to fatalistic attitudes toward existing suffering. Ethical frameworks promoted by bodies like the World Health Organization often focus on alleviating suffering and improving quality of life, rather than preventing existence altogether. These critiques underscore the ongoing complexity and contentiousness of antinatalist philosophy within contemporary ethical discourse.

Antinatalism in Literature and Culture

Antinatalist philosophy, which posits that bringing new sentient life into existence is morally problematic or undesirable, has found significant expression in literature and culture throughout history. This philosophical stance is rooted in the belief that existence is fraught with suffering, and that non-existence spares potential beings from harm. The antinatalist perspective is not merely a modern phenomenon; its themes can be traced back to ancient texts and have been explored by a variety of authors, playwrights, and thinkers.

In classical literature, antinatalist sentiments appear in works such as Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, where the chorus famously declares that “not to be born is best.” This motif recurs in various cultural traditions, reflecting a deep-seated ambivalence about the value of life. In the modern era, the philosophy is most closely associated with the writings of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, who argued that life is characterized by suffering and that procreation perpetuates this cycle. Schopenhauer’s pessimism influenced a range of literary figures, including Thomas Hardy and Samuel Beckett, whose works often grapple with themes of futility, despair, and the burdens of existence.

Contemporary literature continues to engage with antinatalist ideas. South African philosopher David Benatar’s book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence has become a foundational text in modern antinatalist thought. Benatar’s arguments have inspired both philosophical debate and creative responses in fiction, poetry, and film. The antinatalist perspective is also evident in dystopian and existentialist literature, where characters frequently question the ethics of reproduction in a world marked by suffering and uncertainty.

Culturally, antinatalism has influenced artistic movements and public discourse. Visual artists, filmmakers, and playwrights have explored the implications of non-procreation, often as a response to concerns about overpopulation, environmental degradation, and the ethical responsibilities of parenthood. These cultural expressions serve to challenge prevailing pronatalist norms and invite audiences to reconsider the assumed value of bringing new life into the world.

While antinatalism remains a minority position, its presence in literature and culture underscores the enduring human struggle with existential questions about suffering, meaning, and the ethics of creation. The ongoing engagement with antinatalist themes reflects a broader philosophical inquiry into the nature of existence and the responsibilities we bear toward future generations. For further philosophical context, organizations such as the British Philosophical Association and the American Philosophical Association provide resources and forums for discussion on these and related topics.

Legal and Societal Implications

Antinatalist philosophy, which argues that bringing new sentient life into existence is morally problematic or undesirable, has significant legal and societal implications. While antinatalism remains a minority viewpoint, its influence is increasingly visible in debates about reproductive rights, environmental policy, and population ethics.

Legally, antinatalism challenges traditional frameworks that prioritize procreation as a fundamental human right. Most international human rights instruments, such as those overseen by the United Nations, recognize the right to found a family and to decide freely on the number and spacing of children. Antinatalist arguments, however, question whether there should also be a recognized right not to procreate, or even whether society should discourage procreation in light of concerns such as overpopulation, resource depletion, and the potential suffering of future generations. While no country has adopted explicit antinatalist policies, some legal systems have engaged with related issues, such as the right to access contraception, sterilization, and abortion, which can be seen as enabling individuals to act on antinatalist convictions.

Societally, antinatalism intersects with cultural, religious, and ethical norms that often valorize parenthood and the continuation of family lines. In many societies, procreation is closely linked to social status, economic security, and cultural identity. Antinatalist perspectives can therefore provoke controversy, as they challenge deeply held beliefs about the value of life and the responsibilities of individuals to their families and communities. Organizations such as the World Health Organization and the United Nations Population Fund address population issues from a public health and development perspective, but generally stop short of endorsing antinatalist positions, instead focusing on reproductive choice and access to family planning.

The societal implications of antinatalism are also evident in contemporary discussions about climate change and sustainability. Some environmental advocates argue that reducing birth rates is essential to mitigating ecological crises, a stance that overlaps with certain antinatalist arguments. However, these positions raise ethical questions about autonomy, coercion, and the potential for discrimination, particularly against marginalized groups. As such, mainstream policy bodies emphasize voluntary, rights-based approaches to population and reproductive health, rather than prescriptive or coercive measures.

In summary, while antinatalist philosophy has not been codified into law or mainstream policy, it continues to provoke important debates about the ethical, legal, and societal dimensions of procreation, individual rights, and collective responsibility for future generations.

Contemporary Movements and Advocacy

Contemporary antinatalist philosophy has evolved from a largely theoretical discourse into a set of organized movements and advocacy efforts that engage with ethical, environmental, and social concerns. Antinatalism, broadly defined as the philosophical position that argues against procreation, has found resonance in various communities worldwide, particularly in the context of growing anxieties about overpopulation, environmental degradation, and the ethics of suffering.

One of the most prominent contemporary antinatalist thinkers is David Benatar, whose book “Better Never to Have Been” articulates the asymmetry argument: that coming into existence is always a harm, and thus procreation is morally questionable. Benatar’s work has inspired academic debate and grassroots activism, with online forums and organizations dedicated to discussing and promoting antinatalist ideas. These communities often intersect with environmentalist and childfree movements, sharing concerns about the impact of human activity on planetary health and individual well-being.

Advocacy groups such as the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (VHEMT) have gained international attention for their radical stance. Founded in the early 1990s, VHEMT promotes the idea that humans should voluntarily cease reproducing to allow Earth’s biosphere to recover from anthropogenic pressures. While VHEMT is not a formal organization but rather a loosely affiliated movement, it has been influential in raising awareness about the environmental consequences of population growth and the ethical implications of bringing new life into a world facing ecological crisis.

In addition to environmental arguments, contemporary antinatalist advocacy often addresses issues of consent and suffering. Proponents argue that since potential offspring cannot consent to being born, and since life inevitably involves suffering, it is more ethical to refrain from procreation. These arguments are discussed in academic philosophy, bioethics, and increasingly in public forums, podcasts, and social media platforms, reflecting a growing interest in the practical implications of antinatalist thought.

Some antinatalist advocacy intersects with legal and policy debates, particularly in countries facing resource scarcity or environmental stress. While no major government or intergovernmental body officially endorses antinatalism, organizations such as the United Nations have highlighted the importance of reproductive rights, family planning, and sustainable development, which align with some antinatalist concerns, albeit from a different perspective.

Overall, contemporary antinatalist movements and advocacy efforts represent a diverse and evolving landscape, engaging with philosophical, environmental, and ethical questions about the value and consequences of human procreation in the modern world.

Future Directions and Philosophical Challenges

Antinatalist philosophy, which argues that bringing new sentient beings into existence is morally problematic or undesirable, continues to provoke debate and inspire new lines of inquiry. As the world faces unprecedented challenges—ranging from environmental degradation to questions about the ethics of procreation in the face of suffering—antinatalism is likely to remain a significant philosophical position. Looking ahead, several future directions and philosophical challenges are emerging within this field.

One major future direction involves the intersection of antinatalism with environmental ethics. As concerns about overpopulation and ecological sustainability intensify, antinatalist arguments are increasingly being considered in policy discussions about reproductive rights and environmental responsibility. Organizations such as the United Nations have highlighted the impact of population growth on resource depletion and climate change, prompting some ethicists to revisit antinatalist positions as part of broader sustainability debates.

Another area of development is the relationship between antinatalism and advancements in biotechnology. With the advent of genetic engineering, assisted reproductive technologies, and the potential for artificial intelligence, new questions arise about the moral status of creating life under conditions of uncertainty or risk. Philosophers are now examining whether the ability to control or enhance future generations strengthens or weakens antinatalist arguments, especially in light of the World Health Organization‘s emphasis on the right to health and well-being for all individuals.

Philosophically, antinatalism faces ongoing challenges regarding its foundational premises. Critics question whether the asymmetry between pain and pleasure, as articulated by thinkers like David Benatar, is as clear-cut as proponents suggest. There is also debate about the scope of moral consideration: should antinatalism apply only to humans, or to all sentient beings? This question is particularly relevant as animal welfare organizations, such as the World Animal Protection, draw attention to the suffering of non-human animals.

Finally, antinatalism must grapple with cultural, religious, and existential objections. Many societies view procreation as a fundamental good, and religious traditions often frame life as inherently valuable. The challenge for antinatalist philosophers is to engage with these deeply held beliefs while articulating a coherent and persuasive ethical framework. As global conversations about suffering, responsibility, and the future of humanity evolve, antinatalism will continue to adapt, facing both new opportunities and enduring philosophical challenges.

Sources & References

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- World Health Organization

- United Nations

- University of Oxford

- American Psychological Association

- United Nations Population Fund

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement

- World Animal Protection